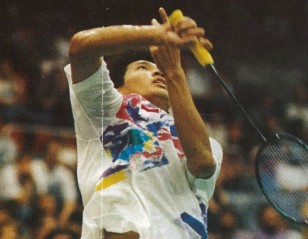

Momota, in the Eyes of his Opponents

What does it mean when a top-15 player in the form of his life admits to feeling ‘blank’ against Kento Momota? What does it mean when such a player struggles with routine shots that he could otherwise play blindfolded?

Was it simply a case of Sai Praneeth having an off-day in his semifinal? Or was there something else – rhetorically speaking, a sort of hypnotic spell – that caused battle-tested and hungry challengers such as himself to feel worn out while facing the guile of the left-hander?

These were the undercurrents in Kento Momota’s startlingly comfortable journey to his second title at the TOTAL BWF World Championships 2019 in Basel last month. The defending champion arrived in Basel with the cloud of his Sudirman Cup final letdown hovering over him; by the end of the week he had burnished his credentials with a performance that was staggering on many levels.

The title was his with six straight-games victories. Out of the 12 games played, six were won in single digits. And there was only one game – one – in which he lost over 13 points. The final itself would turn out to be perhaps the most lop-sided in history – a 21-3 whipping that left most watchers nonplussed. A 21-9 21-3 verdict in a World Championships final?

So what exactly was going on? And what did his victims make of their debacle?

Praneeth, for one, was at a loss for words after his 21-13 21-8 capitulation, just a day after achieving the biggest result of his life, a World Championships medal.

“I was pushing the pace but not getting points, and I was getting mentally tired and I didn’t know exactly what to do. I was attacking, he was taking it.”

Still looking caught in the spell that his opponent seemed to have cast on him, Praneeth went on:

“He plays according to the opponent, he can vary the game whenever he wants to. That is a big plus point for him. He has a lot of patience and a lot of variations. He can read opponents. He has something different from others which makes him tough to beat. I was a bit blank today, there’s not much to say. We will figure it out… someday.”

The only opponent who did give Momota some trouble was HS Prannoy, in the first game of their third round match. The Indian came from behind to level at 19. That’s as far as he got. Looking back, Prannoy could only muse at the tiny gaps that his opponent had exploited.

“There were a couple of crucial mistakes at 15 and 17 or 19 that could’ve gone either way. Mentally it was tough that I could not close out the first. It was probably running in my mind, during the first 11 points, and probably the game shifted.”

Prannoy zeroes in on Momota’s placement of shots that extends the difficulty for opponents. Forcing opponents to run an extra step or two on every shot might not seem a lot, but over the course of a match the incremental gains build up to something much bigger.

“There are certain shots that come from a different angle especially from Lin Dan and Momota. Those kind of strokes you don’t get to play on an ordinary day. They keep coming and you have to move extra on that and probably that’s where you get tired. There are less things that you can counter on those strokes – you need to be either really fast, or you need to be even more skilful than him. Someone like me, I have to run and take those, and I have to wait until I get a really good chance.

“I scored a lot of points in the first game with good attacks, and at a couple of junctures he picked up those crucial ones in the big rallies which would have otherwise gone my way. He didn’t score much with his attack. He was rallying and controlling the shuttle.

“He keeps it down all the time. From the left-handers you get really tough angles, especially on the crosscourt drops, which you don’t get from a (right-handed) player’s overheads; you have to run one more step, which you (usually) don’t do, as you are generally moving further to your right-hand side on the crosscourt drop. So these are a couple of things which are disturbing because you know it’s coming but you have to run a couple of metres more for that and probably at the end of a 55-minute match, that counts.”

The final was unusual on many counts. Anders Antonsen had also progressed without losing a game – in fact, having got a first round walkover, he’d played one match less than Momota. His semifinal against Kantaphon Wangchaoren had taken him 48 minutes. But in the final, after standing his ground in the early exchanges, Antonsen slipped into quicksand, winning just six of the last 40 points.

Antonsen would say he’d just been too tired to mount a challenge. Even so, his struggle with even routine shots mirrored Praneeth’s. It wasn’t just that Momota was playing well – he was also making them play badly.

“In the beginning he made some mistakes and I thought I had a chance, but once he got started, he played good quality and I was too tired to do anything,” said Antonsen.

Momota will know that a week such as this is extraordinary even for him; whatever spell he has cast cannot last. That was why, not long after his win, he talked about reinventing his game.

“I cannot stick to my current style, for my opponents will start reading me, so I have to work on other areas,” said Momota. His opponents may well wonder what else he has in store.

World Championships News

Lessons Learnt, Parting Perspectives 14 September 2019

Kidambi Srikanth – A Search for Form 13 September 2019

Recap: Upsets at the World Championships 10 September 2019

Recap: Memorable Matches of the World Championships 8 September 2019

Highlights of the World Championships 7 September 2019

Played ‘Two’ Perfection – Basel 2019 4 September 2019

Badminton, Ice Hockey and the World Championships 4 September 2019

Three-Event Titan – 25th Edition World C’ships 3 September 2019

Legends of ’77 – 25th Edition World C’Ships 31 August 2019

Para Badminton Event Comes to a Close – Basel 2019 27 August 2019

Wristy Trickery Wins the Day – Basel 2019 26 August 2019

Great Comeback Falls Short – Basel 2019 26 August 2019

Mixed Doubles ‘Great Wall’ Intact – Basel 2019 26 August 2019

Antonsen Bows to Momota’s Class – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

Gold – At Last! – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

Poveda Makes It a First for Peru – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

Legend Who Broke Records and Paved the Way for Future Stars –... 25 August 2019

Ray’s a Real Sport – 25th Edition World C’Ships 25 August 2019

China Take Two Gold – Basel 2019 25 August 2019

‘Upsetting’ Night for China – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Antonsen’s ‘Insane’ Dream – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Glasgow ’17 on the Cards – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Five Down, Seventeen to Go – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Sindhu Assures Herself: Tomorrow Will Be Different 24 August 2019

Para Badminton Athletes Turn It Up a Notch – Basel 2019 24 August 2019

Flaming Dane Set Courts Aglow – 25th Edition World C’Ships 24 August 2019

Antonsen Delivers for Europe – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Du/Li Stand Tall After 2-Hour Epic – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Kantaphon Leads Thailand’s Record Haul – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Sensational Session for India – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Tall Order for Standing Men – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Crowd Pleasing Superstar – 25th Edition World C’Ships 23 August 2019

Teenage Shuttler Meets His Idol – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

Wheelchair Top Seed Toppled – Basel 2019 23 August 2019

‘Two’ Much Trouble! – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Intanon Survives Scare – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

BWF Statement – TOTAL BWF World Championships 2019 22 August 2019

Belated Birthday Blitz! – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Back Problem Doesn’t Stall Jia Min – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Girl Power – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Group Rounds Move into Main Draw – Basel 2019 22 August 2019

Lessons from the Seventies – 25th Edition World C’Ships 22 August 2019

Women Getting in Gear – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

German Shock for Fifth Seeds – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

I Feel at Home says Mroz – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

The Power of the Mind – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

Minions Crash Land at Worlds Yet Again – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

Suzuki Banks on Experience Over Age – Basel 2019 21 August 2019

Nagahara ‘Mixing It Up’ – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Jia Min Ousts Top Seed – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Lin’s Challenge Sputters Out – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Mazur On Track to Retain Crown – Basel 2019 20 August 2019

Trading One Set of Wheels for Another 20 August 2019

Ouseph Exits Stage, Bids Goodbye – Basel 2019 19 August 2019

Chou Survives Danish Test – Basel 2019 19 August 2019

A Title Dedicated to a Battle Against Cancer 19 August 2019

Draw Provides an Even Playing Field for All 18 August 2019

Para-llel Event a Unique Experience for Badminton Fraternity 18 August 2019

An Occasion to Cherish for Jaquet – Basel 2019 18 August 2019

‘100 Watt Smash’ that Lit Up Lausanne – 25th Edition World C’Ships 17 August 2019

Preview: Worlds of Opportunity 17 August 2019

By Chou’s Side 16 August 2019

Satwik/Chirag to Miss World Championships 16 August 2019

Indian Pair Blazes a Trail 15 August 2019

Awesome Threesome of SU5 – Para Badminton World C’Ships 14 August 2019

Life Lessons, From Coach Kim Ji Hyun 14 August 2019

Free of Pressure, Antonsen Senses His Chance 13 August 2019

Ahsan/Hendra Play it Cool Despite Hot Form 11 August 2019

England Duo Anticipate Fruitful Week in Basel 10 August 2019

Women’s Singles Re-Draw – TOTAL BWF World Championships 2019 9 August 2019

Winny Will Need Support: Liliyana Natsir 8 August 2019

Sports Upbringing Gives Edge to Poveda 7 August 2019

World Championships Draw Released 5 August 2019

Marin, Shi Join Axelsen on Sidelines 5 August 2019

New Para Badminton Chapter Unfolds in Basel 1 August 2019

Injured Axelsen Withdraws From World Championships 31 July 2019

From Malmo to Basel – 25th Edition World C’Ships 30 July 2019

Famous Five and the Good Old Days – 25th Edition World C’Ships 19 July 2019

Revisiting a Hero: Sigit Budiarto 11 July 2019

History Beckons Zhang Nan 10 July 2019

Chen To Lead China’s Charge 9 July 2019

19 Days Left To Register for World Coaching Conference 26 June 2019

Marin on the Mend and Eyes Return 22 June 2019

Two Months To Go – World C’Ships Countdown 19 June 2019

Li & Liu – Stepping Up When It Matters 7 June 2019

Ivanov & Sozonov Rekindle The Fire 3 June 2019

Tien Minh – Veteran Still Chasing His Dreams 2 June 2019

Confidence Boost for Dutch Duo 1 June 2019

Matsumoto & Nagahara: Rapid Ascent to Pinnacle 8 May 2019

Tai Eases into Top Gear 25 April 2019

Zhao Yunlei Star Speaker at Coaching Conference 24 April 2019

‘The Physical Level Has Gone Up’ 22 April 2019

Memories of Lausanne 1995 20 April 2019

Momota Sets the Pace, but Speedbreakers Lurk 18 April 2019

BWF and Total Celebrate Five Years of Partnership 18 April 2019

Badminton Thrust into Bright Lights – World C’Ships 13 March 2019

Gold and Glory for Arbi – Throwback ’95 World C’ships 19 February 2019

GoDaddy Extends Major Events Partnership with BWF 11 February 2019

Star speakers assembled for BWF World Coaching Conference 2019 30 January 2019

Singles Champions – Down the Ages 20 December 2018